At Birth, Open Source Was About Saving Money, Not Sharing Code

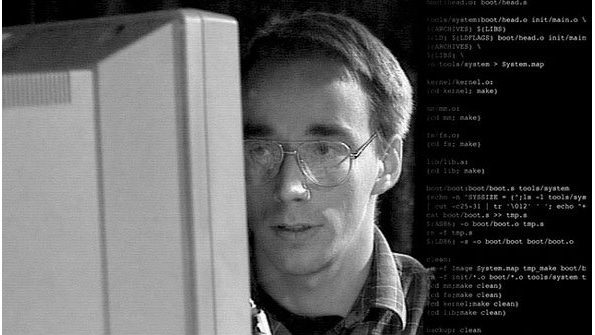

Linus Torvalds and the early supporters of the Linux project were interested primarily in a free-as-in-beer operating system, not ensuring that source code would be freely accessible.

Open source is all about sharing, keeping code open and providing universal access. That, at least, is the received wisdom that has helped guide open source programmers and companies for the last two decades. But a look at the history of open source projects such as Linux suggests that sharing and openness were not actually the primary motives of their founders. Here's why.

N.B.: This is the first in what will, with any luck, turn into a series of posts about the history of free and open source software, which I am researching for (what will hopefully become) a book. I thank my ever-generous editor here at The VAR Guy for, first, allowing me to take a break from coverage of day-to-day open source news items to work on this book and, second, letting me use this site as a platform for exploring some of the ideas that are emerging from my ongoing research.

Update: In an email dated April 27, 2015, Richard Stallman asked me to make clearer the distinction between GNU, the Free Software Foundation (FSF) and open source. As he correctly pointed out, GNU is not a movement; it is an operating system. The FSF is the movement. Further, according to the email, Stallman is "not a supporter of open source; what I stand for is free software. What I say is an example of the thought of the free software movement." Lastly, Stallman states that his impetus for developing GNU was "a rejection of proprietary restrictions on software, not commercialization as such." In light of these statements, this article should be read as an observation primarily about the early history of Linux and the self-defined open source movement that launched in 1998, rather than about GNU and the FSF.

Since the introduction of the term "open source" in the late 1990s, the movement's founders have positioned the sharing and openness of code as the sine qua non of open source software development. Eric S. Raymond, in his canonical essay, "The Cathedral and the Bazaar," contended that the sharing of code made development more efficient, since, "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow."

A similar line of reasoning predates Raymond's rise to prominence, and even the introduction of Linux. As far back as the early 1980s, Richard Stallman, the founder of the GNU project and the man some authorities have called the "last true hacker," declared that the source code of software should be freely shared because "the Golden Rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it."

So, from an early date, advocates of open source development argued that open code is essential for two reasons: First, it's simply a superior way to program; and second, there's a moral imperative to share.

That all sounds grand. And it's certainly true that both the functional and moral dimensions of open code are key motivations for many open source programmers today.

Linux <1.0: Free as in Beer, not as in Freedom

But here's where the history gets complicated: If you look at what the early GNU and Linux crusaders were saying about their work, and read beyond the occasional references to the functional and moral imperatives of keeping code open, it becomes clear that the sharing of code was only a secondary consideration—or, in some cases, not even something the leading figures mentioned at all.

When Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux, famously announced in a newsgroup post in August 1991 that he was "doing a (free) operating system"—which, at the time, had no name, but which in short order became known as Linux—the message was all about making it free as in free beer, meaning the new OS would not cost anything to use. No one was talking about the code being open, or otherwise using the adjective "free" to mean freely shared.

In the very first response to Torvalds's post, a user wrote to express interest in the Swedish-speaking Finnish grad student's work, noting that, in contrast to Minix, the prevailing Unix-like OS for personal computers before the advent of Linux, Torvalds's new OS was going to be free. Again, the word meant "no-cost," not "open source."

The mantra about sharing source code did not develop until later in Linux's history. And the arguments that are familiar to open source supporters today coalesced only in the late 1990s, when Raymond and other collaborators officially launched a campaign to promote "open source"—a term which, by the way, was not even invented until 1998, long after Linux's founding.

It's also telling that, initially, Torvalds released Linux under a license that simply prevented users from making money off of it. It wasn't until later that he adopted the GNU General Public License, or GPL, that Stallman and his cohort had created to keep software code publicly accessible, regardless of whether it had a commercial use.

The story runs deeper than this. There's a lot to say, too, about how Stallman's GNU movement was, in the first place, a reaction to the commercialization of software more than to concerns over the shareability of code. And about how the early hackers who supposedly gave rise to the open source movement had, in the 1970s, happily hacked away on proprietary Unix platforms whose source code was not available to them. (The fact that the proprietary Unixes failed to work well on the cheap personal computers that hit the market circa 1990 was the major impetus for people such as Torvalds to built a new type of Unix; for them, the issue was keeping Unix affordable by making it work on low-cost computers, not creating open code.)

But that's all fodder for a longer post—or, fingers crossed, book chapter. Until then, thanks for reading.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like