What's the most successful company in open source history? Red Hat (RHT) and Canonical would probably top most people's lists. By one measure, however, VA Linux is far and away the most explosively popular Linux company to ever exist. That's if you measure success based on the highest value of its stock, which peaked and then fell dramatically 16 years ago.

What's the most successful company in open source history? Red Hat (RHT) and Canonical would probably top most people's lists. By one measure, however, VA Linux is far and away the most explosively popular Linux company to ever exist. That's if you measure success based on the highest value of its stock, which peaked and then fell dramatically 16 years ago.

If you haven't heard of VA Linux, you probably grew up in the post dot-com bubble age. Once upon a time, the company was a huge presence in the open source world.

Founded in 1993 as VA Research, the company known in its heyday as VA Linux initially sold computers with Linux preinstalled, aiming to compete with the likes of Dell. The company expanded rapidly, boasting $100 million in annual sales by 1998. In the same year, it received capital investments totaling $5.4 million from Intel and Sequoia Capital. The next year, an additional $25 million in funding arrived from an assortment of other backers.

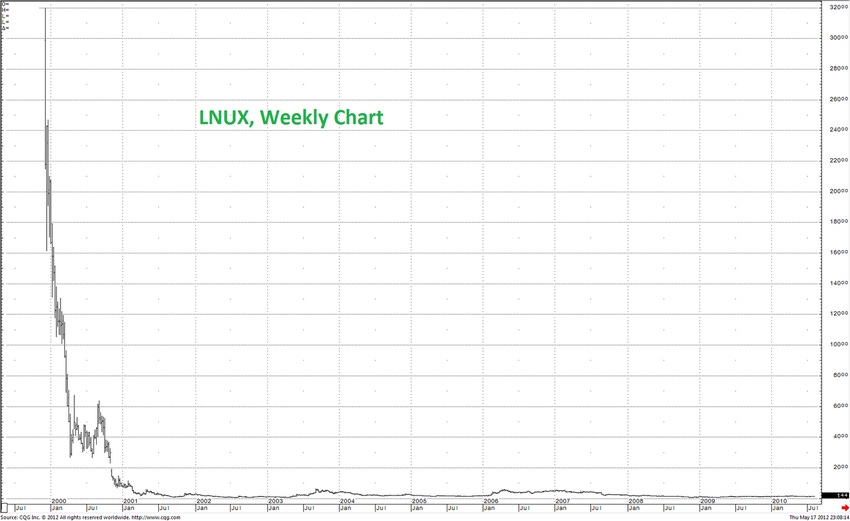

On December 9, 1999, to great anticipation, VA Linux became a publicly traded company, operating under the stock symbol LNUX. Priced initially at $30 per share, the company's stock gained 698 percent in its first day of trading, the highest rise in NASDAQ history.

In the event, however, the momentum of VA Linux did not endure. A year after the company's stock began trading publicly, LNUX was valued at only $8.49 per share. In short order, the company had gone from being the most popular open source outfits on Wall Street to one of the tech industry's greatest failures.

Accounting for VA Linux's Fall

To most observers at the time, the astounding rise and fall of VA Linux reflected the wild nature of the broader Internet dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, when overvaluation of technology companies was a routine occurrence. The New York Times, which summarized the company's initial public offering with the headline, “A Tiny Company with Dim Prospects Goes Public with a Bang,” was pessimistic about VA Linux's outlook even before the stock flopped.

Yet VA Linux's lackluster public launch was not the result of the dot-com bust alone. Its fate was also attributable to its attempt to compete in the desktop market, where it fared no better against entrenched proprietary competitors than ventures such as Corel Linux—another ambitious open source operation that landed hard—did in the same period.

In addition, VA Linux suffered from a lack of strong contradistinction from other desktop and server hardware manufacturers at the time. Selling computers with Linux and GNU software preinstalled does not a unique value-proposition make, either in the late 1990s or now. Plenty of other vendors offered similar products during this period. VA Linux learned the hard way that selling open source-friendly hardware was not enough to set it apart from the crowd.

Life After Financial Collapse

Yet, despite the bursting of its initial bubble, VA Linux survives today as a testament to the commercial viability of media related to FOSS software. In early 2000, the company began shifting its focus away from selling computer hardware after it acquired Andover.net, which owned a variety of news outlets that catered to the hacker crowd. The next year, VA Linux changed its name to VA Software and excised itself from hardware sales entirely.

After a series of subsequent mergers, the company today operates as Geeknet Inc., and continues to focus on websites and other media offerings for the FOSS niche. Last July, GameStop acquired Geeknet.

Being acquired by a company that caters to gamers and does not have anything in particular to do with open source software may be a lackluster ending for what was once a spectacularly valuable Linux business. So it goes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like